Table of Contents

If you’re a broadcast engineer pulling double duty as IT support, you already know the drill. You walk into the station planning to work on transmitter maintenance or optimize your STL link. Instead, you spend three hours troubleshooting why a workstation won’t finish installing updates, or worse, why an automation system won’t boot after an overnight update went sideways.

Microsoft’s Windows Update process has become one of the most frustrating aspects of managing broadcast technology infrastructure. For engineers at smaller stations who wear multiple hats, it’s not just annoying. It’s a massive time sink that pulls you away from the work that actually keeps your station on the air.

The Update Process Shouldn’t Be This Hard

When Windows Update works, it’s invisible. But when it doesn’t, you’re stuck running command line tools like DISM and SFC, clearing update caches, stopping and restarting services, editing registry keys, and maybe even performing an in-place upgrade just to restore functionality.

Microsoft’s official troubleshooting guide lists dozens of potential error codes. Each one represents a path down the rabbit hole. Is it corrupted files? Permission issues? Insufficient disk space? A conflict with third-party software? Maybe the Windows Update service itself is broken.

Recent updates have made things worse. In October 2025, Microsoft acknowledged that the KB5050094 update was causing 0x800F081F errors due to missing language packs. The fix required either another patch or an in-place upgrade using Windows installation media.

Earlier this year, the August 2025 security updates broke Windows reset and recovery tools on nearly every supported version of Windows 10 and Windows 11. Users attempting to use the “Reset this PC” feature found that the process would start and then immediately roll back. Microsoft released an emergency out-of-band patch, but by then the damage was done.

The Broadcast Station Ripple Effect

For a single engineer managing the IT stack at a radio or TV station, these failures are more than technical headaches. They’re operational emergencies.

A workstation that won’t complete updates becomes unreliable. It might freeze unexpectedly. It might fail to boot. And if that workstation runs something critical, like traffic software, automation systems, or playout control, you’ve got dead air risk.

The same goes for studio systems. Modern broadcast operations are built on IP-based infrastructure. STL links run over IP. Automation talks to the network. Even transmitter monitoring is web-based. When Windows decides it’s time to install updates at 3 a.m. and something goes wrong, you find out when you get a call that the station is off the air.

Broadcast Radio’s support documentation explicitly warns about the risks. Updates can redetect hardware, reinstall drivers with default settings, or enable features like Audio Enhancements that break soundcard performance. And if an update is already installed and waiting for a reboot, leaving the system in that state for days can cause severe instability.

Microsoft Keeps Breaking Things

The pattern has become predictable. Microsoft releases a cumulative update. Within days or weeks, widespread reports emerge of failures. The company acknowledges the issue. Then it releases either another patch or a registry workaround.

In August 2025, Windows updates caused severe stuttering and lag with NDI streaming software. This impacted broadcasters using OBS and other tools for remote production. Microsoft initially suggested a workaround involving NDI transport protocol changes. A fix didn’t arrive until September.

Also in August, smartcard authentication failures followed the October 2025 update. Systems using CSP-based RSA certificates suddenly couldn’t authenticate. Microsoft deployed a Known Issue Rollback to resolve it.

October brought more chaos. The KB5066835 update broke WinRE recovery tools, leaving USB keyboards and mice completely nonfunctional in the recovery environment. It also caused localhost connection failures that rendered some systems essentially unusable. Microsoft issued KB5070773 as an emergency fix.

These aren’t minor bugs. They’re core functionality failures that Microsoft’s own testing should have caught.

The Command Line Gauntlet

When updates fail, you end up at the command line. The standard fix workflow looks like this. Open Command Prompt as administrator. Stop the Windows Update service, BITS, Cryptographic Services, and MSI Installer. Rename the SoftwareDistribution and catroot2 folders. Restart the services. Run DISM with /Online /Cleanup-Image /RestoreHealth. Run SFC with /scannow. Reboot. Try the update again.

Maybe it works. Maybe it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, you start digging through CBS.log to identify corrupted files, download the specific cumulative update from the Microsoft Update Catalog, extract the .msu and .cab files, manually copy missing files into a source folder, and run DISM again with the /Source parameter.

This is not an exaggeration. Microsoft’s own documentation describes this exact process as the fix for Windows Update corruptions.

For a broadcast engineer who needs to be at a transmitter site, this kind of troubleshooting is a productivity killer. You’re not improving infrastructure. You’re fighting with an update system that should be invisible.

Registry Hacks and Workarounds

Sometimes the fix involves editing the registry. To manually unpause Windows updates without triggering automatic downloads, you edit HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\WindowsUpdate\UpdatePolicy\Settings and change PausedFeatureStatus and PausedQualityStatus to 0. Then you delete five time-related entries in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\WindowsUpdate\UX\Settings.

Want to force a manual update check from the command line? That’s not straightforward either. You can trigger w32tm /resync for time updates or use PowerShell modules like PSWindowsUpdate, but there’s no single, reliable built-in command to force an update scan without also triggering automatic installation.

These workarounds exist because Microsoft’s update system is opaque and doesn’t give users enough control. The system assumes it knows best. When it doesn’t, you’re stuck digging through community forums and Reddit threads for solutions.

The Forced Obsolescence Problem

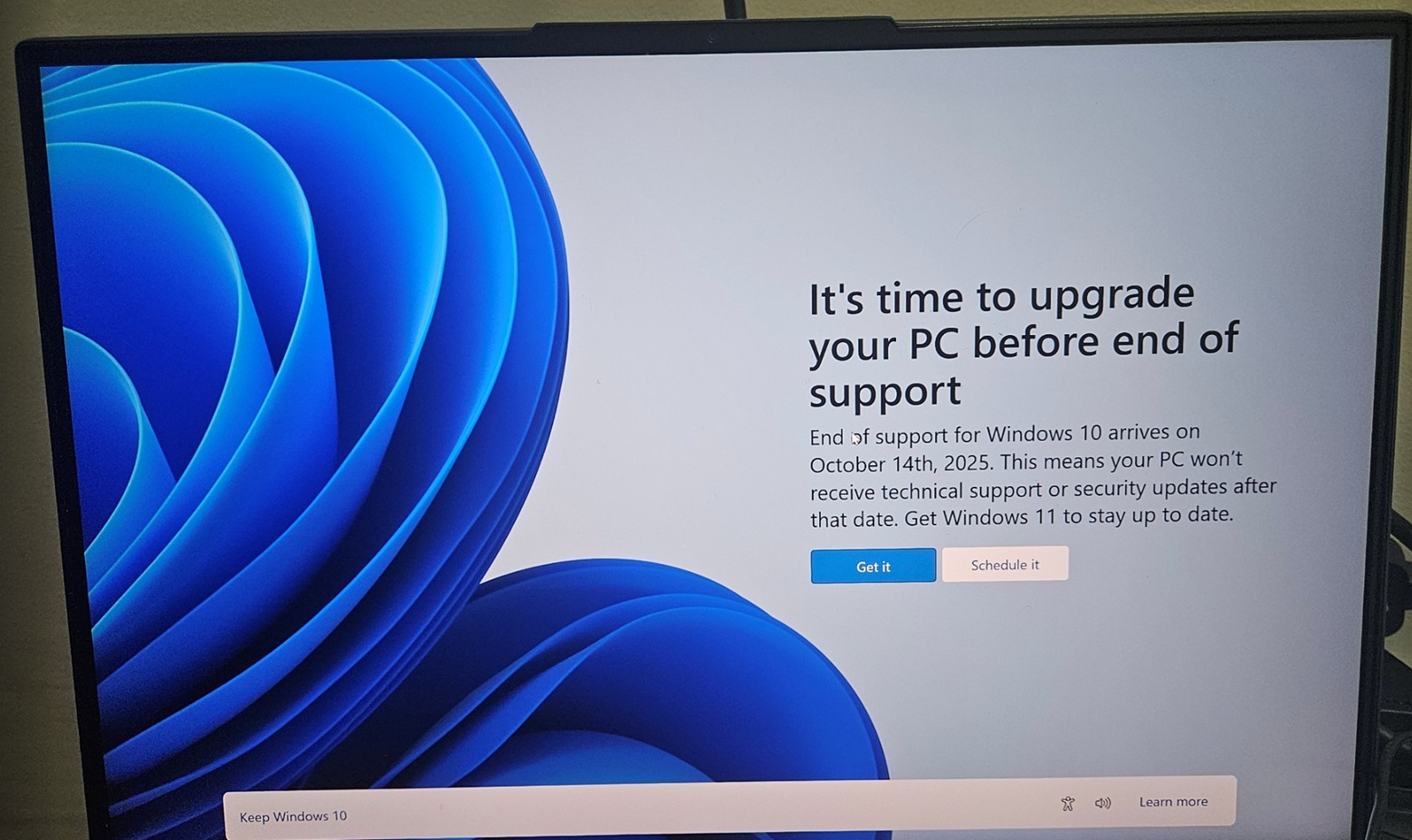

Now layer on Microsoft’s hardware requirements for Windows 11. The operating system requires TPM 2.0, Secure Boot, and a CPU from Intel’s 8th generation or AMD’s Ryzen 2000 series or newer.

Windows 10 support ended on October 14, 2025. Machines that don’t meet Windows 11’s requirements are now officially unsupported. That includes millions of perfectly functional computers with 7th-gen Intel processors, older Ryzen chips, or motherboards without firmware TPM support.

For broadcast stations running older but stable hardware, this is a disaster. A Dell workstation from 2016 with a Skylake i7 processor can run Windows 10 flawlessly. It handles automation, playout, and office tasks without issue. But Microsoft says it’s obsolete.

Critics, including former Microsoft engineers, have called out the arbitrary nature of these requirements. While TPM 2.0 and Secure Boot provide security benefits, the CPU restrictions are less defensible. Older chips can run Windows 11 fine in terms of performance. Microsoft excludes them to reduce driver support complexity and push hardware-based security features, but the practical result is forced obsolescence.

The environmental impact is staggering. Microsoft is contributing to e-waste by forcing users to discard functional hardware. Guillaume Pitron and other experts have documented the resource scarcity and environmental toll of mining rare earth metals for electronics. Making millions of working computers “obsolete” accelerates that damage.

What Stations Can Do

If you’re managing Windows systems at a broadcast facility, here’s what actually works.

Pause updates aggressively. Use Group Policy or registry tweaks to delay feature updates and control when quality updates install. Schedule updates during off-peak hours, and never let them auto-install during critical dayparts.

Test updates on non-critical systems first. Don’t deploy the latest cumulative update to your automation server the day it drops. Wait a week. Let other people find the bugs. Check BleepingComputer and The Register for reports of widespread issues.

Keep offline installers and bootable media ready. Download cumulative updates from the Microsoft Update Catalog and store them locally. Have a Windows 10 or Windows 11 USB installer on hand for in-place upgrades when the update system completely breaks.

Document your workarounds. When you find a fix, write it down. Build a runbook for common Windows Update failures specific to your environment. You’ll need it again.

Consider alternatives for critical systems. If possible, run automation and playout on dedicated hardware with tightly controlled update policies. Some stations keep critical systems on LTSC editions of Windows that receive far fewer updates.

The Bigger Picture

Microsoft’s update process isn’t just inconvenient. It’s a fundamental design failure that wastes time, breaks systems, and forces expensive hardware upgrades on functional machines.

For a broadcast engineer juggling transmitter maintenance, network optimization, and day-to-day IT support, Windows Update failures can easily consume days of work per year. That’s time you’re not spending improving infrastructure, upgrading facilities, or solving real problems.

The forced obsolescence through TPM and CPU requirements makes it worse. Stations running perfectly good hardware are now stuck choosing between paying Microsoft for Extended Security Updates, upgrading to Windows 11 on unsupported hardware using registry hacks, or replacing thousands of dollars worth of equipment that still works fine.

It shouldn’t be this hard. An update system should be reliable, predictable, and transparent. Microsoft’s isn’t. Until that changes, broadcast engineers will keep spending too much time fighting with Windows instead of doing the work that matters.

Get On The Air